Dan & Viktora

– To åledrivkvaser

Af

MORTEN GØTHCHE

The Trade and Maritime Museum’s yearbook 1961 was written by Christian Nielsen about »Boatbuilding on Fejø and the Danish eel drifters«. His successor as advisor to vessel owners interested in restoration, architect Morten Gøthche, has read the article, talked to Christian, interviewed fishermen, dived into archives and carefully reviewed two of the Nielsen family’s preserved drifters. On this basis, he gives a detailed account of how the eel drifters “Dan” and “Viktoria” are to be restored.

Since opening in 1969, the Viking Ship Hall has collected a number of recent vessels within the Nordic cultural area: Faroese boats, a church boat from Dalarna, western and northern Norwegian boats and others, which in form and construction have the same common features as the exhibited Viking ships. The Viking Ship Hall’s boat collection has over the years been used in several different pedagogical and research contexts. In recent years, the school service at the Viking Ship Hall has worked with a teaching offer with the topic »Fisherman on Roskilde Fjord, 1850-1925«. So far, the Faroese boat collection has been used for this purpose, but in the longer term they would like to be able to use local boat types from the fjord, or similar types from other places. It therefore came very conveniently when the Viking Ship Hall in 1981 had the opportunity to acquire an old eel drifter from Fejø. It was precisely one of the boat types that has been used extensively on Roskilde Fjord.

Christian Nielsen has in his article »Boatbuilding on Fejø and the Danish eel drifters« described these eel drifters in great detail, and since he, as the grandson of the boat builder who built these vessels, was born and raised in this tradition, it was therefore natural that he was consulted at the inspection and purchase of the drifter. The boat was in Nyord near South Zealand and could reportedly be acquired for five fathoms of firewood – a price the boat had at one time been traded for. Christian Nielsen was able to ascertain that it was one of his grandfather’s drifters. The fisherman who owned the boat had retired and the drifter had been lying in the harbor for a year without having been used. After a cheerful fart about the price over a cup of coffee, the price fell to a symbolic price of a penny, but with the condition that the boat under no circumstances may be sailed from there on its own keel.

In the same year, the author of the article had also acquired an old eel drifter from Fejø. The boat was at that time in Dragerup harbor near Holbæk but had previously been resident in Roskilde. Here Christian Nielsen had also seen it and had recognized it as one of his grandfather’s drifters.

With the purchase of Viking Ship Hall’s eel drifter, the boat’s papers came with: A certificate of nationality (measurement letter) from 1938 and a supervision book from 1933. It appeared that the boat’s name was »Viktoria« with the identification number K 206. It is stated that the all-purpose drifter »Viktoria« was built in 1904 by boat builder Christian Nielsen, Fejø, for fisherman Jens Peter Jensen, Askø. The registration number was then N 485, and it had the identification dimensions: Length 26.5 feet, width 8.6 feet and depth 3.3 feet. The vessel was measured at 4.42 gross registered tons. It was Jens Peter Jensen’s third drifter of this name. In 1930 the drifter was sold to fisherman Oskar Rasmussen, Bandholm, and in 1936 it was sold on to fisherman Peter Erik Andersen, Sallerap Strand and given the registration number K 206. Shortly afterwards it was sold to fisherman Helge Ewald Johansen Stolt, Nyord, who then had it, until Viking Ship Hall in 1981 bought it. The inspection book states that »Viktoria« got its first engine in 1912. It was a single-cylinder four-stroke engine from Houmøller in Frederikshavn at 10 HP. When the Viking Ship Hall took over the drifter, there was an HSA engine, type »95« from the limited company Herman Svendsen, Glostrup Dieselmotorfabrik. The engine, which is two-cylinder and at 15 HP, has been installed sometime after the war.

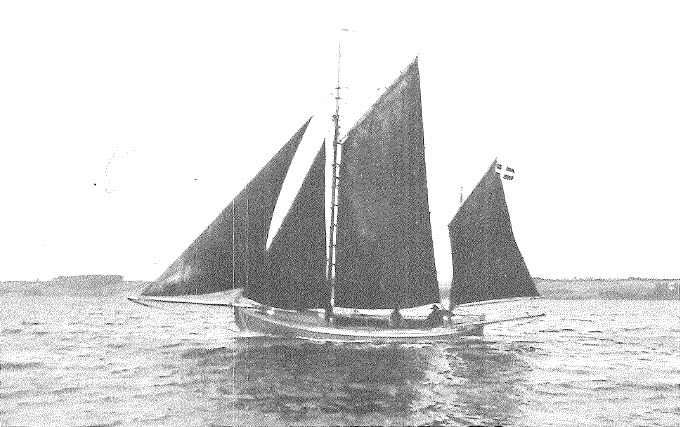

big jib, the very broad mizzen and the white-painted spars and mastheads: Jensen owned three fishing

smacks called Viktoria, all built by Christian Nielsen of Fejø; the first in 1895, this one in

1897 and the third built in 1904 which is now in the Viking Ship Museum. Photo: Danish Maritime

Museum.

This course of development is by no means atypical. From pure sailboat to sailboat with auxiliary propeller and up to a boat with a full-power engine and support sail, “Viktoria” has, despite changing times and new technology, managed to survive as a commercial vessel. With its nearly 80 years on the keel, it has, of course, undergone some changes and repairs. First and foremost, during the engine installation, it has been necessary to carry out certain conversions, and in this connection, decks have been laid aft around the engine and an engine cowling has been built over it. Later, a small wheelhouse was fitted, which could be hung when the drifter used sails. However, it has only been relevant in the interwar years and during the war, while the sails have hardly been used much after the war. The original mast has also been replaced with a lower mast. “Viktoria” had at the time a gaff mainsail, on which the original bracket still sat. Helge Stolt has at one time put a larger roof over the front hatch, but otherwise no other significant changes have been made to the décor. At the time of purchase, the drifter was fitted with a false keel, and the hole for the centerboard was closed with a sheet pile. “Viktoria” has also had a higher toe rail. Helge Stolt still had the hauling ring for the jib and the lying traveler for the stay foresail, which the Viking Ship Hall got with the purchase.

When purchasing the private drifter, no paperwork was included, and the previous owner could not remember the name of the person from whom he had bought the boat. However, he had found out that the drifter had originally been called “Dan”. Whether it was »Dan« of Askø built in 1908 for fisherman Gregers Rasmussen, (mentioned in Christian Nielsen’s article), I could not be sure. Gregers Rasmussen was no longer alive], but in a review of the phone book for Askø I found fisherman Verner Rasmussen, who turned out to be a son of Gregers Rasmussen. He could then also confirm that he and his father had been owners of the drifter. On the same occasion I was told that he had the original gaff with fittings and that he still had the old jib2 lying in the loft. It had only been used for a few years and was in good condition. In addition, he had two ring brackets for the mast as well as some old blocks, a nationality certificate and a supervision book lying around.

As it appears from the article in the Trade and Maritime Museum’s yearbook, »Dan« is quite rightly built by Christian Nielsen, Fejø, for fisherman Gregers Rasmussen, Askø. The year of construction is stated to be 1908. In the list of vessels domiciled in the Maribo-Bandholm customs district from 1908 and in a later copy from 1933, however, the year of construction is 1907.

The registration number was then N 428. The identification length was 26.8 feet, the width 9.0 feet and the depth 3.3 feet. The gross registered tonnage was set at 4.68 and the net tonnage the same. From the inspection book from 1915 it can be seen that »Dan« got its first engine in 1914. It was a 472 HP four-stroke Frederikshavn engine. “Dan” was initially only used for fishing with an eel driftnet, but later switched to being used for bottom net fishing. Verner Rasmussen, who was born in 1911, has fished with his father since he was a boy (approx. 11 years old), but has only been involved in bottom fishing. Later, Verner Rasmussen and his father used the drifter as a freighter for Qvade, a large grain and feed company in Bandholm, where they, among other things, sailed with grain, feed, coal and other products to the island. When the drifter began to sail with freight was not determined with certainty, but of the nationality certificate from 1933, the gross registered tonnage was adjusted to 5.18 tonnes, and the net tonnage was set at one tonne. The correction was made by the registration office in Nykøbing Falster on 21 September 1935, which also corresponds with a previously submitted survey report dated 7 September 1935. Here, “Dan”, which is described as a half-deck boat with H / S (auxiliary propeller) and well, was in Bandholm for measurement on 9 September 1935.

clearly of fir. The fore-staysail is made fast with a burton, and the centerboard is raised. Photo:

Danish Maritime Museum.

This correction can be linked to the use of the drifter as a cargo boat. The one tone that “Dan” was still marked with at the time of the takeover corresponds to the goal one could imagine, the space on the well deck – the cargo space, could be added to. Verner Rasmussen could also state that “Dan” could load 25 sacks of grain or just over 2.5 tonnes, but then it was also well loaded. Why the original 4.68 tons gross register tonnage is directed to 5.18 tons is not known, but on a later registration sheet, where the boat is also listed with 5.18 tons and 1.00 tons in net register tonnage, the identification length is 8.76 meters (= 27 feet and 11 inches). It is approx. 15 inches more than the measure the drifter was first set for. However, the last known measure corresponds to the actual measure of the drifter, so it must have been measured incorrectly from the start.

After his father’s death in 1958, Verner Rasmussen continued sailing for Qvade until 1963, when a fixed ferry connection was established between Bandholm and Askø. The drifter now had to leave his old place in front of Qvade’s warehouse in favor of the new ferry berth. At one point, while the drifter was sailing like a freighter, the well was taken out and all the bottom planks replaced. A solid ceiling was then placed in the bottom, and the drifter has been given an actual hatch frame. The old mast was replaced with a shorter heavy mast with unloading boom. Later, the “Dan” got a larger engine – a two-stroke “Hein” that could also pull a small unloading winch mounted on the mast.

When asked by the customs chamber in Nykøbing Falster in 1973 whether Verner Rasmussen is still the owner of the half-deck boat “Dan” of Askø, he answers that it was sold to Roskilde Fjord approx. eight years ago (1965). Verner Rasmussen himself has stated that he sold it to a nephew, port assistant Edvin Petersen, Bandholm. However, he only had it for a short time, after which he sold it on to Harald Keldgaard, also from Bandholm. It was here that the boat was converted into a pleasure craft with a wheelhouse and cabin, had a fixed iron keel fitted and fitted with a small low fork a gaff rig. Keldgaard had it for a couple of years and then sold it to a man in Roskilde. In these years, there is a lot of uncertainty about the fate of the drifter. When it was bought in 1975 by fitter Flemming Jørgensen, it had been on land for a year. Flemming Jørgensen bought it primarily to be able to cultivate his hobby as a scuba diver and only discovered after the purchase that the boat had a mast and sail. However, he soon noticed the drifter’s possibilities as a sailboat, increased the sailing area further, and rigged it up with topsails and jibs. Here, however, the old Hein engine could no longer, and it was replaced with an old taxi engine. After 1976 and until 1981, when I bought it, it was based in Dragerup near Holbæk.

Goals for the restoration

As the idea is that the all-purpose drifter ‘Viktoria’ will be used partly for educational purposes and partly by a boating association, there will be a complete return of the drifter with the original sail plan, well and centerboard and of course without engine. With regard to the privately owned drifter, there are also plans for a certain degree of return in terms of hull and rig, while in the longer term a decision must be made as to whether the boat should again have a centerboard and possibly a well. As the engine broke down immediately after the takeover, the boat is currently sailing with an outboard engine of 772 HP.

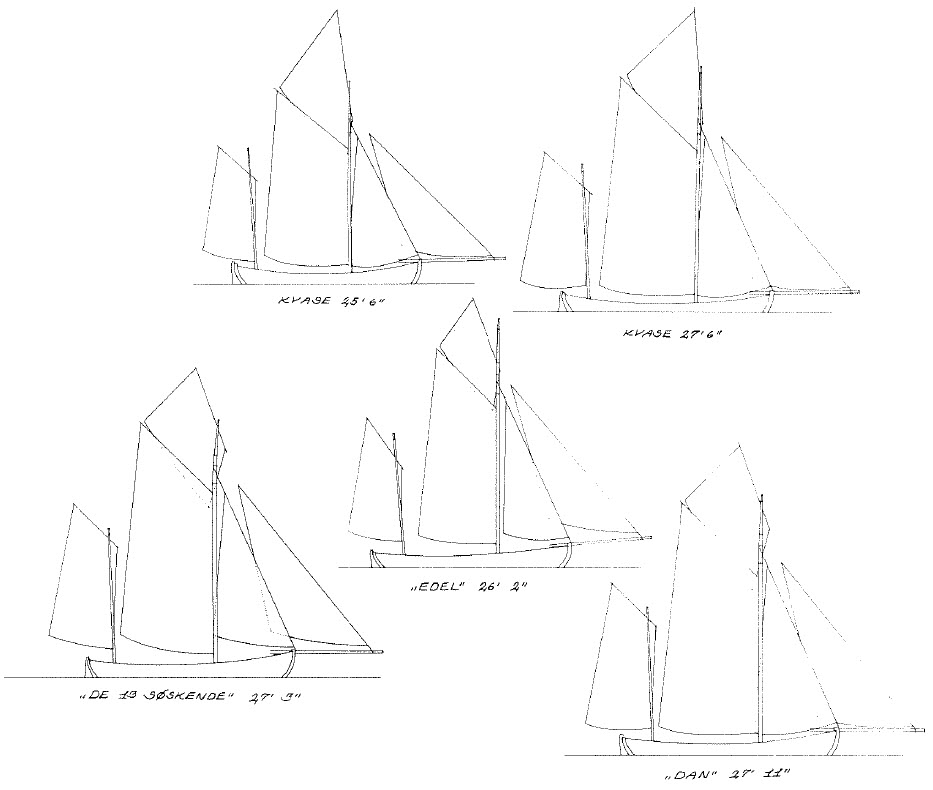

Now the easiest solution would have been to reconstruct the rig of the two drifters after Christian Nielsen’s otherwise excellent survey of “The 13 Siblings”, as it is shown in the article about boat building on Fejø and in the book “Danish Boat Types”, but as previously suggested, should seek, as far as possible, to return the individual vessel to its original appearance. If this is not possible, you should familiarize yourself thoroughly with the tradition that applies to the type of vessel in question, among other things by collecting as much material as possible: photographs, drawings, archives and interviews with old fishermen and others. You will thus have a better basis for carrying out a sensible restoration and repair.

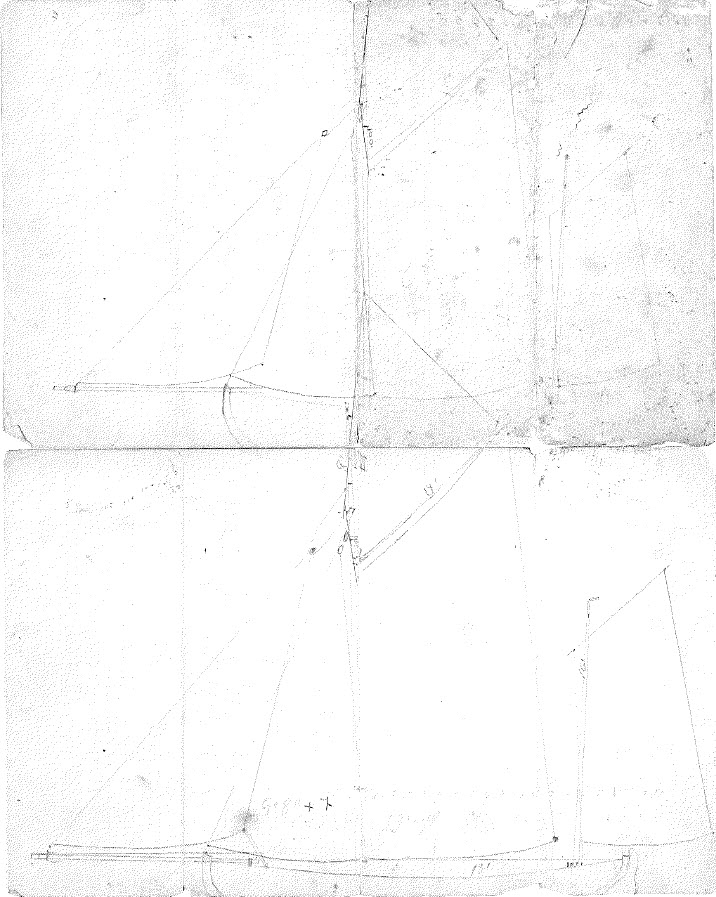

The space between lines has been used as scale. One space = Ifoot. Names of drifters not known

As the preliminary studies have not revealed any photographs of the two eel drifters, there is only the possibility to reconstruct from the existing tracks and then make a rigging that is within the framework of the current tradition. On the other hand, with this double restoration you will have the opportunity to show several variations within the same tradition.

It was only natural to first go to Christian Nielsen, who as the grandson of the old Christian Nielsen has had a direct contact with tradition. In addition to the already reproduced photographs of eel drifters in Christian Nielsen’s article (drifter no. 10 »Edel« from 1898) and in »Danske Båd Typer« (drifter no. 30 »Christian Nielsen« from 1907) he had photographs of four more drifter (drifter no. 8 »Viktoria« from 1897, drifter no. 15 »Elisabeths Minde« from 1900, drifter no. 24 »Aalen« from 1904 and drifter no. 38 »Rigmor« from 1912). There had been another picture of the drifters, but they are now lost. In addition, Richard G. Nielsen’s book »Fra Fjord og Fiskeri« contains another picture of an eel drifter, which is clearly a Christian Nielsen drifter. It is the »Swan« of Hestehaven belonging to fisherman Henrik Hansen (drifter no. 23 built for Jørgen Svendsen, Fejø, 1903).

Christian Nielsen also had some envelopes lying around with various letters and bills from his grandfather’s time, some of which had been used in the article. Only by the case that these things have been taken out of its context are they preserved for posterity. Otherwise, everything else from the boat building on Fejø has been thrown out or burned. Among these papers were three sailing sketches, – two of them of eel-drifters, made by the grandfather. The sail sketches are drawn on lined paper, where the distance between the lines has been used as a measure: A line distance is equal to one foot. In addition to the knowledge that Christian Nielsen had already acquired in his article about his grandfather’s drifters, he could further contribute with new information. In the case of this subject in particular, the source seemed to have been inexhaustible. Finally, conversations with Verner Rasmussen and local fishermen and others on Fejø and Askø have provided a lot of valuable information.

Annex 2

List of those of Chr. Nielsen built Fejø drifters (1894-1914)

(For the accuracy of individual years cannot be guaranteed).

| # | Navn | Name | B.år Year Built | L. | B. | D. | BRT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | „Svalen” | Swallow | 1894 | 25,8 | 9,0 | 3,8 | — |

| 2 | „Anna” | [given name] | 1895 | 24,0 | 8,5 | 3,5 | 4,10 |

| 3 | „Viktoria” „Christiane” | [given name] | 1896 | 26,2 | 8,9 | 3,3 | 4,53 |

| 4 | „Tordenskjold’ | [possibly the namesake of a Dano-Norwegian Vice Admiral] | 1896 | 21,1 | 8,0 | 3,0 | 2,81 |

| 5 | „Dos Santos” | [Spanish for Two Saints? Why?] | 1896 | 30,6 | 10,5 | 4,0 | 7,44 |

| 6 | „Marie” | [given name] | 1896 | 26,2 | 8,9 | 3,3 | 4,53 |

| 7 | „Marie” | [given name] | 1897 | 27,7 | 9,9 | 3,5 | 3,47 |

| 8 | „Viktoria” | [given name] | 1897 | — | — | — | — |

| 9 | „Hjemmet” | Home | 1897 | 18,8 | 6,5 | 3,0 | 2,16 |

| 10 | „Edel” | [given name] | 1898 | 26,2 | 8,9 | 3,3 | 4,81 |

| 11 | „De tre Søskende” | The 3 Siblings | 1898 | 26,6 | 9,6 | 3,3 | 5,37 |

| 12 | „Rigmor” | [given name] | 1899 | 26,0 | 9,0 | 3,6 | 5,29 |

| 13 | „Freja” | [given name] | 1899 | — | — | — | — |

| 14 | „Karens Haab” | Karen’s Hope | 1900 | 26,3 | 8,9 | 3,4 | 5,11 |

| 15 | „Elisabeths Minde | Elisabeth’s Memory | 1900 | 26,2 | 8,9 | 3,4 | 4,96 |

| 16 | „Karoline” | [given name] | 1900 | 24,7 | 8,6 | 3,0 | 3,98 |

| 17 | „Heimdal” | [a Norse god]2 | 1901 | 27,0 | 8,7 | 3,0 | 4,27 |

| 18 | „Inger” | [given name] | 1901 | 26,9 | 9,6 | 3,4 | 5,07 |

| 19 | „Bettie” | [given name] | 1902 | 27,0 | 8,8 | 3,1 | 4,60 |

| 20 | „Valkyrien” | Valkyrie [Norse mythology] | 1902 | 28,2 | 9,6 | 3,3 | 5,18 |

| 21 | „Energi” | Energy [?] | 1903 | 28,2 | 9,6 | 3,3 | 5,27 |

| 22 | „Marie” | [given name] | 1903 | — | — | — | — |

| 23 | „Svanen” | Swan | 1903 | — | — | — | — |

| 24 | „Ålen” | Eel | 1904 | 26,1 | 8,9 | 3,3 | 4,51 |

| 25 | „Viktoria“ | [given name] | 1904 | 26,5 | 8,6 | 3,3 | 4,42 |

| 26 | ukendt | unknown | 1905 | — | — | — | — |

| 27 | „Maagen” [The Gull] | Gull | 1905 | — | — | — | — |

| 28 | „Alida” | [given name] | 1906 | 28,1 | 9,4 | 3,2 | 4,82 |

| 29 | „Anna” | [given name] | 1906 | 26,0 | — | — | — |

| 30 | „Chr. Nielsen” | [given name and surname] | 1907 | 28,1 | 9,3 | 3,4 | 5,82 |

| 31 | „Ella” | [given name] | 1907 | — | — | — | — |

| 32 | „Dan” | [given name] | 1908 | 26,8 | 9,3 | 3,3 | 4,68 |

| 33 | „Vinterflid” | Winter Diligence [perhaps the name of a larger ship on which the owner previously served] | 1908 | 26,5 | 9,1 | 3,4 | 4,96 |

| 34 | „Willy” | [given name] | 1909 | 27,7 | 9,6 | 3,4 | 5,20 |

| 35 | „Viking” [Viking] („Kristiane”) | Viking [given name] | 1909 | 28,3 | 9,9 | 3,3 | 5,22 |

| 36 | „Maagen” | Gull | 1910 | 27,7 | 9,6 | 3,4 | — |

| 37 | „De 13 Søskende | The 13 Siblings | 1911 | 27,3 | 9,9 | 3,3 | — |

| 38 | „Rigmor” | [given name] | 1912 | 27,3 | 10,0 | 3,3 | — |

| 39 | „Kamma” | [given name] | 1914 | 28,0 | 10,0 | 3,8 | 6,07 |

| 40 | „Laxen” | Salmon | 1914 | — | — | — | — |

(1896) and Hjemmet (1897) were one-man vessels.

Tradition

Christian Nielsen mentions in his article that with the exception of the first two, the length of the drifters was from 26 to 27 feet between the stem and stern post. From a review of the register of vessels, we have the identification measurements for almost all drifters. The length of the mark is measured from the aft edge of the stern and to the front edge of the bow, i.e., approx. one foot longer than the measure between the stem and stern post. Here is the general picture that before the turn of the century it was predominantly 27-foot drifters that were built, and 28-foot drifters after the turn of the century. There are indeed two or three 25-foot drifters at the beginning of the period. On the other hand, the drifters No. 4 «Tordenskjold« at 21 feet and No. 9 »Hjemmet« at only 18 feet fall a little outside. Christian Nielsen believed that they were eel drifters, the so-called single-man drifters. Quite outside also, drifter no. 5 »Dos Santos« falls to just over 30 feet, – almost as big as the German drifter »Minna« in Danish Boat Types (31 feet and 6 inches). With its 26.5 feet or approx. 25 feet and 6 inches between the bows, “Viktoria” represents the smaller drifters of the tradition, while “Dan” with its approx. 27 feet between the stems represent the large drifters.

At the same time as the drifters grew in size, the rigging was also made larger in relation to the length. To make the fishing that only lasted for approx. four months, from May to September, effective, it was important to be able to operate with even the weakest winds. The smallest of the sail sketches is perhaps one of the first small drifters. The length is approx. 24 feet. The mast is from the deck and up to the flagstaff truck approx. 25 feet and up to the shroud landing approx. 18 feet. Otherwise, the mast length was between 30 and 32 feet, depending on the size of the drifter. The masts have not been longer than 32 feet or the 16 cubits that Christian Nielsen mentions in his article. The actual sketch of the sail varies only slightly from drifter to drifter. A significant difference is that they have either lug topsails or gunter topsails (the latter is actually also a lug topsail, but where the yard is vertical).

A characteristic feature of Christian Nielsen’s eel drifters is the low freeboard, and for most drifters, eye-catching rear-facing stem, the slightly elongated and at the ends full deck plane and the sharp lines of the underwater hull. Due to the plank keel, the cross section is relatively low with a rather weak rise on the garboard and a harmonious layout of the other planks upwards. It is demonstrable that towards the end of the period the drifters were built wider and thus fuller in relation to the length than the earlier ones, for example drifter no. 38 »Rigmor«, which with its 27.3 feet in length had a width of 10 feet. It was the widest and lowest of all the drifters, but at the same time also the best sailing.

is reconstructed from a photograph of Edel built in 1898. The fourth is drawn on basis of Christian

Nielsen’s survey of De 13 Søskende. The fifth a reconstruction of Dan. Drawing by the author

The construction

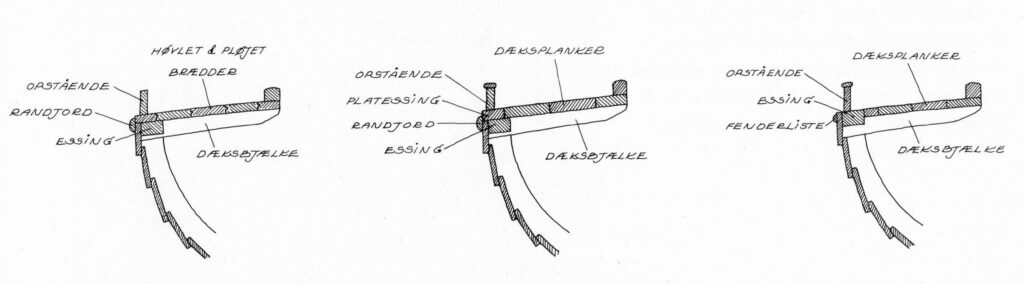

There have hardly been great variations in the construction itself. The well could e.g., be arranged differently according to the buyer’s own wishes. Christian Nielsen mentions in his article that the first drifters were built from cheaper materials than the later ones. For example, the deck on the first drifters was simply made tongue and groove planks boards. The boards ran all the way to the edge of the top strake and were planed smooth with this. Later, the rub rail (fender strip) came on and covered the plank ends. On the later drifters, the deck planks were made of 1-1/4 inch thick pine planks, and here the planks ran out on a covering board on top of the actual gunwale, or they ran directly out on the gunwale. The deck planks, now also caulked, could be either five-inch planks (“The 13 Siblings”) or seven-inch planks (“Dan” and “Rigmor”). It was not so good with the wide planks. When the planks dried, the seams became very open and thus the deck leaked. Some did so with the set iron (caulking iron) striking an extra seam down the middle of the plank. A weakness in the construction was the deck beams, which over time tended to sink, due to the patches at the ends either breaking or rotting away. Many drifters therefore at one time also installed shelves.

a. Deck planks of ordinary tongue and grooved boards planed smooth with the upper strake and covered with the edge rail (fender strip). Note no rail on top of the toe rail, as also appears from the picture of »Edel« from 1898.

b. The construction on the later drifters (as on »Dan« and »Viktoria«)

c. A simplification of the construction that should reduce the risk for rot attack, as used on »De 13 Søskende«.

Drawing by the author.

The deck plane

The deck plan could vary somewhat from drifter to drifter. On the measurement of “De 13 Søskende”, the low frame on the deck opening runs aft in a smooth curve, while the front frame is straight with rounded corners. The cockpit is shaped similarly – almost like an oval. This did not seem to have been the case on all the drifters. In the photographs of »Elisabeths Minde« and Jens Peter Jensen’s drifter »Viktoria« from 1897, you can see that the aft frame is also straight with rounded corners. The cockpit apparently has a rectangular shape. In both cases, the cockpit is covered by a corresponding rectangular cover. The bitt, which is intended for mooring and on which the innermost end of the jib-boom rests, is on »De 13 Søskende« designed as two large cleats, through which the cross-piece sits. This design is probably transferred from the German drifters, which simply instead of the cross-piece could have a small mooring drum with a pawl ring. More common has probably been with a bitt in the traditional design with two bitt supports and on the aft edge of these a cross-piece. This design can be seen on several drifters, and one has also survived on the two drifters mentioned. In the photographs of »Elisabeths Minde« and »Viktoria«, it looks as if the cross-piece is just over two short longitudinal cleats on the deck.

Photo: the author

Masts and Spars

The article states that the masts were made of 6×6 inch pine beams. The other spars of round spruces. It was likely Pomeranian fir that was used. Originally, this was probably a term for a species of pine of special quality introduced from Pomerania. Later, it has become a quality term for pine species with a strong red color and dense core formation. On delivery, the beam was rigidly cut 6 inches, and the finished mast was to be 6 inches in diameter from approx. one meter above the deck and up to the shroud landing. Thus, by first chopping the round stem square and then round again, the cross section consisted of approx. 2/3 core wood, which gave a rigid mast. Above the shroud fittings, the mast was tapered to approx. 2 inches at the flagstaff truck. The top should be straight at the leading edge, and if the whole beam already had a natural curve, this should be turned aft so that the top would face forward. When later there was a pull aft from the peak halyard, and the gaff at the same time pressed under the shroud fittings, especially during takedown, the top tended to tilt aft, and it did not look good.

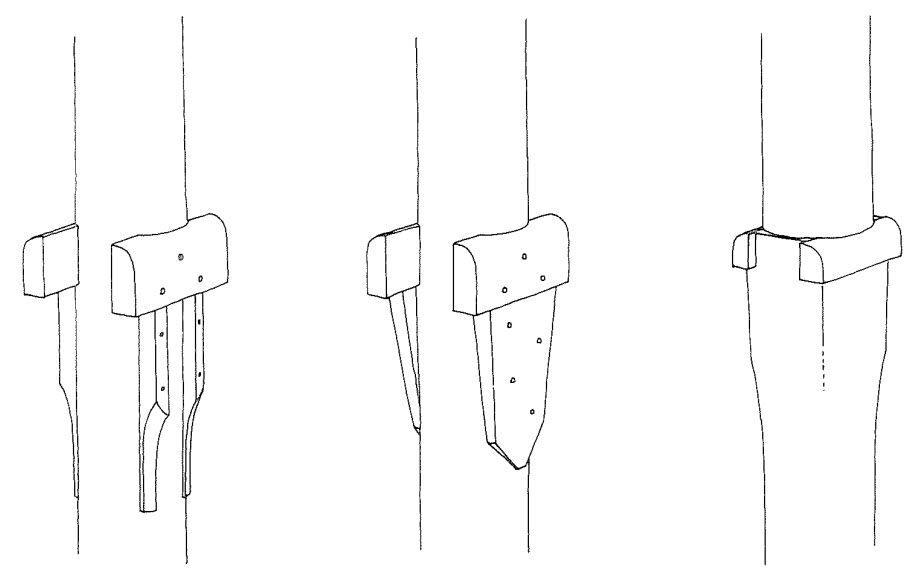

The shroud landing could have been made in the traditional way with bolsters embedded in the mast and supported by cheeks [center, in image below]. Instead of cheeks, the bolsters could also be supported by two finely shaped moldings (as on the model of »De 13 Søskende«) [left, in image below] or they could be completely without cheeks [right, in image below]. The masts were also made of spruce. The spruce masts make themselves known by the fact that they taper evenly from the deck and up to the flagstaff truck. With a spruce mast, it was important to take off as little as possible, as it, unlike the pine beam, is in the outer shell that the spruce has its greatest strength. The mast just needed to be straightened. Often you could see bark remains in the small hollow under the branches, which of course had to be stuck away. »Dan« probably had a spruce mast, as the original ring fittings for the mast are smaller in diameter than they would have been for a pine mast

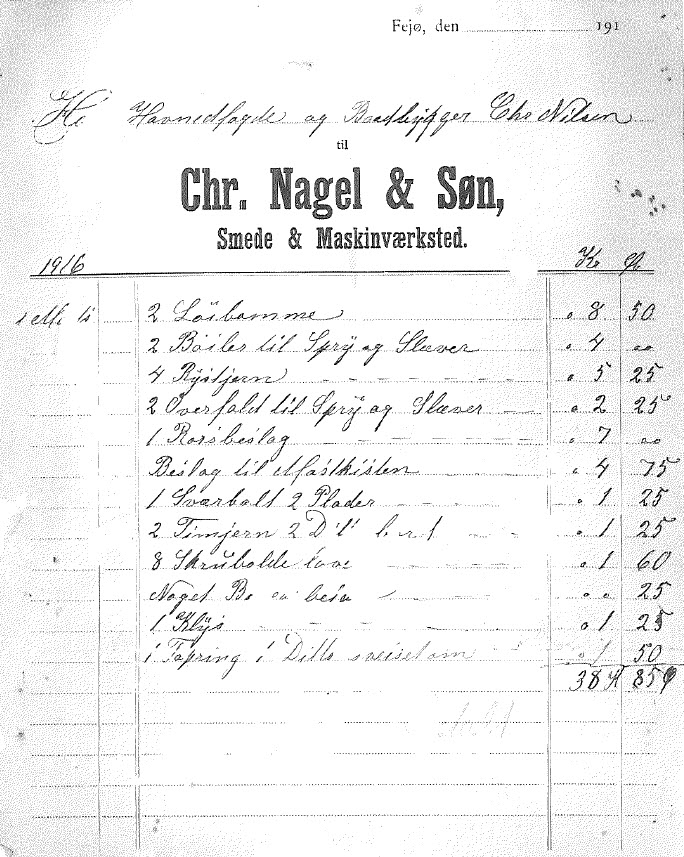

Fittings

The iron fittings for the drifters were, as mentioned, made by the local blacksmith or by a blacksmith in Bandholm. The two løjbomme are the iron bars on which travel the sheet block for the mainsheet and the foresheet, respectively. Bøjler til spryd og slæber are the fittings for the jib boom and drift boom boom, respectively. The “fold overs” are the brackets that hold the inner end of the jib boom and drift boom in place. In addition, this bill lacks the parral band for the gaff and the hauling rings for the jib, etc. The parral band, or patent parral, and the hauling ring may have been standard fittings that could have been ordered home from the capital.

The sails

As mentioned during the rigging, the proportions of the sail sketches were roughly the same. There could be certain variations, e.g., whether it should be a lug topsail or a gunter topsail, a larger or smaller jib, a wider mizzen, etc. In a letter from Ole Strandby from Astrupvig, he refers to »Niels Holms or Jens Peters (Jensen) the first (drifter» Viktoria «), which he thought had a suitable rigging, but that the mizzen could well be 6 inches wider and the topsail a lot deeper«. (Jens Peter Jensen’s second drifter »Viktoria« from 1897 has clearly had a wider mizzen). On Frans Eggert’s drifter »Chr. Nielsen ‘, the stay foresail has become too large, and it has been necessary to put a reinforcing patch in the head.

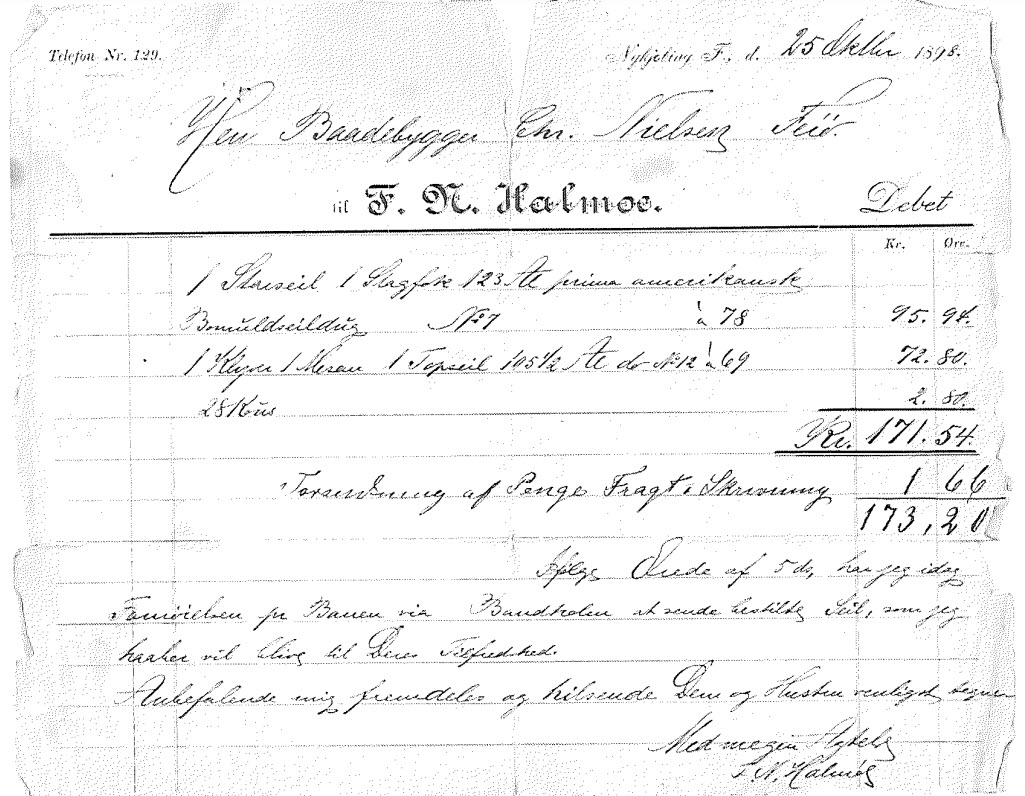

On the sail sketch of »De 13 Søskende«, the clew of the mainsail and the foresail are disproportionately high up. On the two sail sketches from the old Christian Nielsen’s hand, both the mainsail and foresail go much further down, which also seemed to agree with the drifters depicted. The sails were likely sewn at sailmaker N.E. Halmø in Nykøbing Falster, which had a reputation for sewing good sails, but other sailmakers were also used. Some fishermen sewed their sails themselves, often from old sails from larger ships or from the pleasure craft. On a bill from sailmaker Halmø Nykøbing Falster (p. 93), it appears that the cloth used is “excellent American cotton canvas. Mainsail and foresail are sewn from No. 7 cloth, mizzen, jib and topsail of No. 12 cloth. There is nothing about the width of the tablecloth used, but it was probably not the traditional two-foot cloth. If you count the number of cloths on the known sailing sketches, you get an average width of 48-50 cm. On »De 13 Søskende«, however, 56 cm. With this width and with the amount of sailcloth that has been included according to the bill, it corresponds very well to the sailing area (approx. 65 m2), the finished sail has. The original jib for »Dan« is sewn from similarly narrow cloths, and the width here is approx. 53 cm. Of preserved original sails from a Christian Mortensen drifter from 1922, one finds a similar cloth width, but where it turns out to be a very wide cloth, which is divided in the middle with a blind seam. In the picture of Jens Peter Jensen’s second drifter from 1897, very narrow cloths can be seen on the jib, and also on the mizzen, but less clearly. It’s about 15 narrow tablecloths in the jib, which is approx. twice as many as usual. Here, too, there may be a wider cloth, halved with a blind seam.

On the survey of »De 13 Søskende«, there are two rows of rope ties on the mainsail and one on the stay foresail. The drifters could also have three rows of knots on the mainsail and two on the stay foresail (the drifter »Chr. Nielsen«). Most of the drifters appear to have had three rows of rope ties on the mainsail, as well as an extra row of holes without ties above them. On »Aalen«, three horizontal lines are sensed at the aft edge of the mainsail immediately above the upper rope string, which resembles batten. These are probably battens, as they are also mentioned in the correspondence with master Halmø regarding Jens Peter Jensen’s drifter. All sails were hand-sewn at that time. Later they were sewn on machine. The hand-sewn were preferred to the machine-sewn. It was believed that the machine-sewn caught wind, as opposed to the hand-sewn, where the selvage was sewn well into the canvas.

Standing rigging

When it comes to the standing rigging, there are only small variations. Shrouds and stays consisted, as mentioned in the article, of twisted iron wire. The iron wire is stiffer than ordinary steel wire, as it has fewer and thicker cords. It has the advantage over the steel wire that the individual cords do not rust over so easily. The shrouds were fitted with lanyards, either in exterior chain plates or in rings in the gunwale inboard of the toe rail. If the chain plates sat outside, they went halfway down the second-highest strake and were bolted to the frames behind. If, on the other hand, the chain plates were inside the toe rail, the irons were stuck down through it and fastened to the side of the corresponding frames. The support of the mast consisted of a shroud span to each side. The shrouds were served on the piece where they lay around the mast and by splices at the thimbles.

The forestay sat a bit above the shroud landing, where it rested with a served eye on a thumb cleat on the stern edge of the mast immediately below the lower ring bracket. The forestay could either have been pierced through a hole in the bow and attached to the bitt, or it could have been shackled directly into an eye on the stem fitting. The first solution looks very neat, especially in connection with the backward-curved stem, which is almost in the direction of the stay, but there is slight rot in the hole in the stem. With the second solution, there is no possibility to adjust the length of the stay

The running rigging

The solution for the individual details in the rigging has depended partly on the drifter’s home, partly on the user’s own ideas and has thus been more varied, while the details in the hull have only depended on the building tradition in question. One detail where there was direct disagreement between boat builder and user was the solution around the peak halyard. On »De 13 Søskende«, the fixed part of the peak fall is fixed on the inner ring of the gaff. The halyard is then reeved over a block in the lower ring on the mast, then back over a block in the outer ring on the gaff and back over a block on the upper ring on the mast and to the deck. Christian Nielsen thought it was the right way to reeve the halyard. This gave a more direct pull on the gaff when it had to be stretched. Nevertheless, all photographs show drifters with the peak halyard reeved opposite – namely with the fixed part on the outer ring on the gaff and the hauling part over the block on the lower ring on the mast. A remarkable detail is the location of the throat halyard block, which is shown in the drawings and model of »De 13 Søskende« sitting above the shroud landing. One might be immediately tempted to believe that the throat halyard block has at some point been moved higher up if the mainsail should have stretched over time and become too high. However, this detail is seen on an original mast from a Christian Mortensen drifter.

The leach rope on the mainsail could either be attached to the mast, as in the model of »De 13 Søskende« and in the picture of »Rigmor«, or lashed to 6-7 mast rings. When the sail was attached to the mast, the rope end was rotated alternately right and left. The fore halyard could either be fastened with a single block in the stay eye, over which the halyard was reeved (»Edel«), or with a double-reeved tackle (the other drifters). The rope end on the fore halyard could also be knotted to the thimble in the foresail’s head and thus at the same time serve as a downhaul. Furthermore, the stay foresail bowline could also be used, either when drifting, or when close hauled (»Elisabeths Minde«). The jib halyard could also sit in several ways. The most common was that the halyard was fixed on the upper ring on the mast and then reeved over a block in the jib’s head and back over a block in the lower mast bracket and to the deck. The halyard could also be reeved in reverse, i.e., with the fixed part on the lower ring (»Elisabeths Minde«), or the halyard could sit alone in the upper ring. Usually, the jib outhaul, which lay over a thumb cleat on the side of the bow immediately above the waterline, served as a bobstay, but the jib boom could also have an actual bobstay (»Aalen« and »Chr. Nielsen«). Then one end of the bobstay was fastened to the bow immediately above the waterline, and at the other end there was a double-reeved tackle with the hauling part led into the deck and fastened to the bitt. Finally, the topsail halyard could have been reeved in two ways, either over a transverse disc hole under the flagstaff truck on the mainmast, or over a block hooked in a ring bracket in the same place (»De 13 Søskende«). The drifters had flag halyards in both masts’ flag staff trucks. On the mainmast, a small windsock or wing was carried on a short pole. When sailing with a mizzen, Dannebrog was carried under the yard arm on the mizzen yard, otherwise the flag was carried on the mizzen top.

Dyes and Colors

Christian Nielsen writes that the drifters were smeared with coal tar at the bottom, and that they were either green or gray on the freeboard. The model of »De 13 Søskende« has a green freeboard, but none of the drifters in the photographs are green on the freeboard. The toe rail was painted white on the outside, as were the cabin trunk sides and the bitt. Whether the drifters were green or gray, the cabin trunk roof and sliding cover were commonly painted green. On Askø and Lilleø, however, brown paint was used. Finally, the gunwale and the toe rail interior were painted with the color that the drifter had on the outside of the freeboard. One had to be especially careful here to get the paint to cover the joint, where the gunwale and the toe rail ran together. One thing that was much debated was whether the white color from the tow rail should continue out onto the stern and further out onto the rudder head. Christian Nielsen’s grandfather was not a supporter of it. He believed that when the fishermen themselves had to paint it, it could easily ‘hang’. It is probably true that one should have been particularly careful with this detail, but when it is made nicely, as e.g. on the drifter »Elisabeths Minde«, it looks quite neat. The cap rail and the rub rail were varnished, as were the remaining part of the sternpost and rudder head, as well as the entire top of the stem.

As mentioned, the deck was also varnished, possibly. mixed in a little English red – it should seal as well. On Askø and Lilleø, the deck could also be painted brown. Masts and spars were usually scraped and oiled. If you thought the masts were a little too light, as the brand new spruce masts often were, you could mix a little ocher in the oil. As can be seen in »Edel« and hinted at Peter Jensen’s »Viktoria«, the mast top and the other roundwoods could also be painted white – something that in certain maritime circles is considered a custom. It is probably transferred from the German drifters where it was common to paint the mast tops. It had the disadvantage that rot attacks easily occurred under the paint layer. Also, the tabernacle and the blocks in the rig were in these cases painted white. Inside, the drifters were smeared with wood tar and the well with coal tar.

Waterproofing of Sails

After a while in use, the sails were waterproofed. The article mentions that they were lubricated with a hot mixture of horse grease, ocher, wood tar and water. The sails were then spread out on the meadow and lay here for a fortnight, where every day the mixture was rubbed well into the sails. When waterproofed with this mixture, they got a yellowish slightly mottled color (the original splitter from »Dan« has this color). The sails could also be impregnated with catechu, but then they became completely “black” (cf. the photograph of »Aalen«). They do not actually turn black, but almost rust red or reddish brown.

Sailing qualities

The high rig and the fine lines of the hull give the immediate impression that the eel drifters from Fejø were well-sailing vessels. This is further emphasized by the fact that the fishermen took every opportunity to race, whether it was on their way to or from fishing or arranged races between the drifters among themselves or with the pleasure craft. The picture of Frans Eggert’s drifter »Chr. Nielsen« shows just such a situation. The image of »Rigmor« is from a race sometime in the 1930s. The steering wheel has been removed (“Rigmor” has at this time got an engine), so it has been better to control with the sails.

The fishermen who sailed the drifters claimed that if they only had sails as good as the pleasure craft, they would be able to catch up with them in a race. You also saw how details from the pleasure craft were transferred to the drifters, for example, as previously mentioned the battens, which are clearly seen on »Aalen«, and which Jens Peter Jensen demanded to get in the mainsail on one of his drifters. Precisely these two fishermen had a reputation for being very avid racing sailors. The purpose of the battens has probably been to get the sail flat out towards the stern so that it could get rid of the air. The drifters were often pressed hard, sometimes so that the water stood right up to the toe rail -yes, even all the way to the side deck, but they were led by old sailors, whether they had sailed in the navy or in the merchant shipping. The drifters had no real ballast – the water in the pond seemed like such. At the same time, the drifters, which were very flat, in themselves had great dimensional stability. To get the right trim on the drifters, you wanted some quantity of bricks in the aft room. It is said that a fisherman from Kolding could not understand why his drifters could not sail. He thought it was built incorrectly – until he was made aware that the extra bricks should be aft of the pond – not in front. When tacking or when close hauled, “beydevind”, as they say on the islands, they only used mainsail and jib and possibly also topsail if it could be carried. Incidentally, the topsail was difficult to get to stand. Mizzen and jibs were seldom used, “… there was too much cloth (sailcloth) in the jib”, i.e., it was too hollow or too baggy. On the other hand, it drew well for a good wind (from beam wind to quarter wind). When at the same time the centerboard had been pulled up a little (less wet surface), the drifters could really get going. Furthermore, it is said that one of the drifters, after the engine had been put in, had been in Bandholm and had a six-inch false keel placed under the plank keel. On the way home, the fisherman noticed, by taking time on the buoys, that the drifter had lost from half to a whole knot in speed. The drifters became better and better sailing throughout the period. The first drifters were narrower and therefore also more upright, while the last drifters that were built were wider, cf. the example of »Rigmor«, and therefore more rigid in it. They were also better sailors. Verner Rasmussen can still remember that »Dan« and Jens Peter Jensen’s drifter »Viktoria« – it must have been the last of his drifters, were very equal. When it was light weather, »Viktoria« ran from »Dan«, but when it started to blow, yes, it was the other way around.

»Dan« and »Viktoria«

At the time of writing, the eel drifter »Dan« is standing by Roskilde Boatyard, which is now owned by Vikingsskibshallen, and awaits the arrival of spring. Inside is »Viktoria«, and here you are in the process of replacing the bad planks in the hull. The project, which is an employment project under Roskilde County, began in the spring of 1982. The project continued in 1983, and it is expected that the hull itself will be completed before the end of the year. Next, the idea is to let a private boating association sort out the actual rigging, so that the drifter can come under sail as early as the spring of 1984. The first season, the privately owned drifter »Dan« sailed with the old yacht rig, but already the following year in 1982 it was rigged up with new masts and spars and a new mainsail. For the time being, the stay foresail from the old rig is sailed, and the mizzen is an old sewn-on Bermuda sail. In return, »Dan«s old jibs came to honor and dignity again and proved to stand completely well.

DAN AND VIKTORIA

Two eel drifters

Summary

[This English summary appeared at the end of the original article]

Since its opening in 1969 the Viking Ship Museum has added a number of recent Scandinavian vessels to its collections: boats from the Faeroes, from northern and western Norway, and a church boat from Dalarne in Sweden, which in form and construction have the same characteristic features as the Viking ships on display. Over the years the Museum’s collection of boats has been made use of in connection with various projects ofa research and educational nature – one of them having as its theme »Fishing in Roskilde Fjord, 1850-1925«. Up to now the craft from the Faeroes have been used for the purpose but it is intended in future to make use of local types of craft from the Fjord. In 1981 the Viking Ship Museum was able to acquire an old eel drifter from Fejø, ofa type which had been used extensively in Roskilde Fjord. In the same year the writer also became the owner ofan old eel drifter from Fejø.

Eel fishing by means of a drift-net was first introduced into Denmark in the 1870s by Pommeranian fishermen who came to Denmark from Rugen in their own boats. Later this method of fishing was taken up by Danish fishermen who bought up the foreign smacks. In the middle ofthe 1890s Niels Christian Nielsen of Fejø, thegrandfather of Christian Nielsen, introduced a Danish built eel drifter which became very popular and had the reputation of being a good sailer (see Christian Nielsen »Bådebyggeriet på Fejø og de danske åledrivkvaser« (Boatbuilding on Fejø and Danish eel drifters) and Wolfgang Rudolph »De pommerske åledrivkvaser og deres betydning for Danmark« (Pommeranian eel drifters and their significance for Denmark), both in the Danish Maritime Museum’s yearbook 1961).

The drifter Viktoria in the Viking Ship Museum was built in 1904 by Christian Nielsen, for Jens Peter Jensen, a fisherman of Askø. Its registration number was N 485 and its dimensions length: 26.5 feet, width: 8.6 feet, draught 3.3 feet, and 4.42 gross register tons. Jens Peter Jensen owned the vessel until 1930, after which it had

various owners. When the Viking Ship Museum bought it, for the token sum of one krone, it was owned by Helge Ewald Johansen Stolt, a fisherman of Nyord. An engine had been first installed in 1912 and by the time the Museum acquired it in 1981 the rigging had been reduced to an auxiliary sail, a larger engine had been installed and a wheelhouse built.

The privately owned Dan was also built by Christian Nielsen on Fejø, in 1908, for Gregers Rasmussen, a fisherman of Askø. Registration number was N 488 and dimensions 26.8 feet, 9 feet and 3.3 feet, with 4.68 gross register tons. For the first few years itwas used for eel fishing with a drift-net. In 1914 it got its first engine. Later it carried cargo for a large corn and fodder merchant, Qvade, in Bandholm, from where it transported various products to Askø. For this purpose the well was taken out and the smack was put at 5.18 gross and 1 net register tons. After Gregers Ramussen’s death his son, Verner, continued this run until 1965 when a regular ferry service was established between Askø and Bandholm. As there was no longer any need for the Dan it was sold off and until 1981 was used as a pleasure craft.

It is intended to restore the Viktoria to its original appearance in 1904. That is, it will again have a well, a drop keel, and a complete set of sails, though of course no engine. The privately owned Dan will only be partly restored as it is to be used as a pleasure boat. The simplest solution would no doubt be to rig the two smacks according to the drawings of De 13 Søskende by Christian Nielsen in his »Danske Baadtyper« (Wooden Boat Designs). However among the material he left after his death were found a number of drawings and pictures of his grandfather’s drifters, so now we have a better foundation for reconstruction ofthe two smacks in question.

First of all reconstruction will be on the basis of existing parts ofthe hull. Afterwards an attempt will be made, as far as possible, to show variations within the same type.

The restoration ofthe Viktoria is now in full swing and is expected to be completed by the summer of 1984. The Dan is also in process of being restored and has been carrying a full set of sails since the 1982 season.